What should you write next?

How to know if an idea is worth pursuing

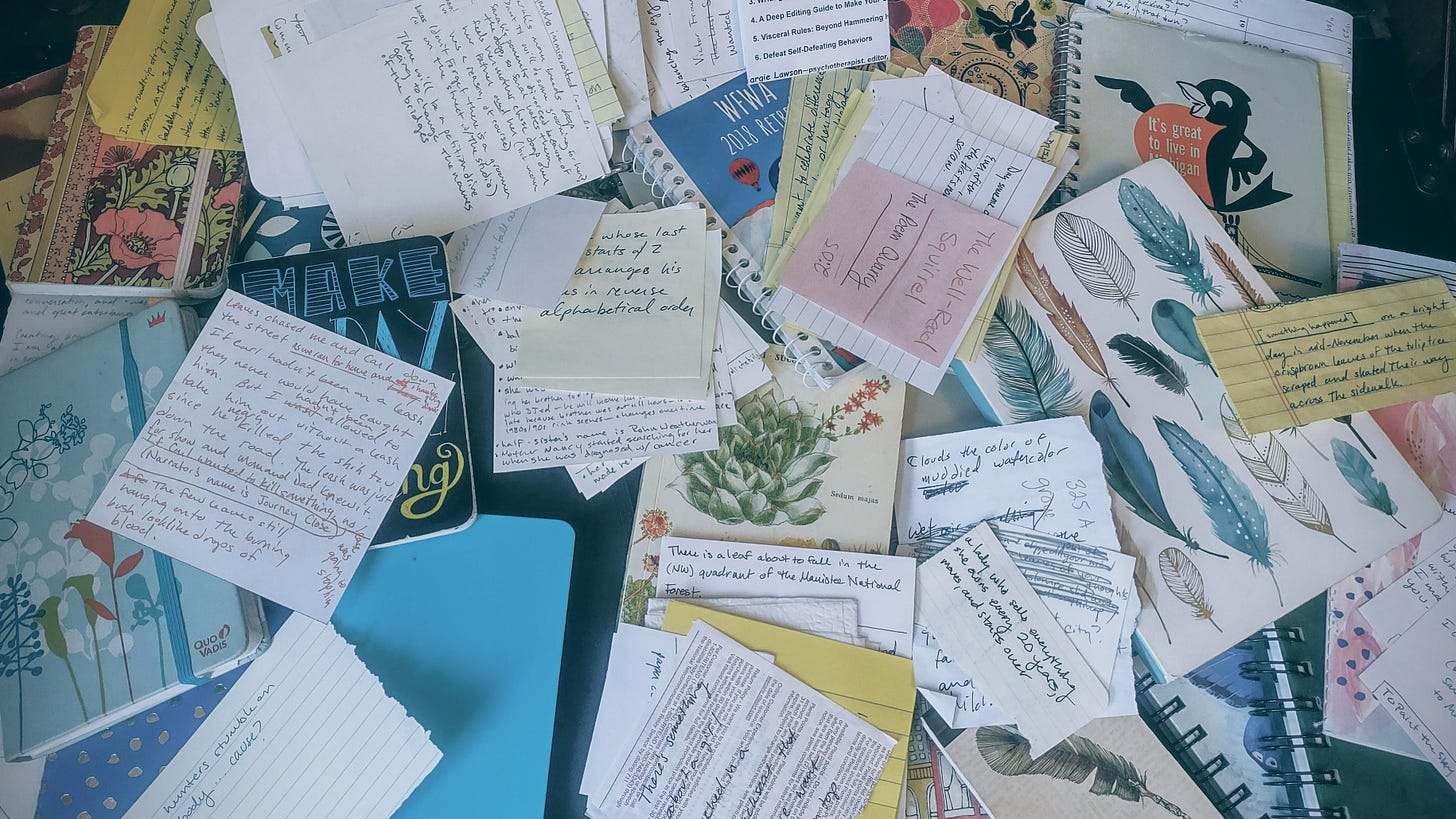

If you’re anything like me—and I suspect you are, otherwise you wouldn’t be here—the inside of your brain might look a little like this.

This pile of words represents nearly 15 years of “writing it down so I won’t forget.” Some scenarios, pulled at random, from these journals, notepads, and scraps of paper:

Something (computer? SD card?) is found in an apartment closet when a new person moves in. What is on it? What does it mean? It creates some sort of responsibility to someone else, which he resists.

A business professional tries to put his competition out of business by getting someone to commit a heinous act with his competitor’s product (a ’la the Ryder truck in Oklahoma City bombing, the Bronco in the OJ murder trial).

A remote long-distance hike. Pilot makes drops of food in big metal bins to sustain hiking party. What if the drop didn’t get made? What happened to the pilot? What will happen with the hikers?

These are the kinds of scenarios that pop into a writer’s head from time to time, and we write them down because they “have potential.” Any one of these ideas could kick off a story because they have inherent conflict and push a character to do something. To make a decision and set off on a course of action that may end in triumph or in disaster.

I also compulsively write down first lines. Again, pulled at random:

I was too young when I fell in love to know enough to worry.

The moon is a rock hung in the sky.

It is yet day and I stumble for the seventh time.

Sometimes, I just record title ideas.

An Exemplary Death

Widows of Great Men

The Weight of Words

I write everything down because a few of those everythings might be something. The question is, how do you know when an idea is worth pursuing? How do you know if it is worth your time to write any more words than that scrawled note on the back of a Qdoba receipt?

Well, you could just dive in immediately and spend months writing 80,000 words only to get to the end and realize (either on your own or with the help of an honest critique partner) that you’ve got a whole lot of nothing special.

Or you could take some time on the front end to work through the various ways the plot might go and the characters might develop, and so have a better idea of whether that magnificently original thought you had while your boss was droning on and on in a staff meeting is worth devoting a huge chunk of your creative energy to over the better part of the year.

You can do such work alone—after all, you don’t want anyone to steal your concept—but it’s so easy to fool ourselves about the brilliance of our own ideas. A better approach might be to do some brainstorming with a writing partner or a small, trusted group of writers with our best interest at heart.

Whether we bounce ideas off other people or we just let them bounce around in our own heads, here are some questions to ask ourselves that might help separate the wheat from the chaff.

Does this idea have inherent conflict? If not, how can it be tweaked so that it does?

Is the conflict actually a conflict? Or is it just an annoyance?

Is the conflict easily solved? One way to determine this is to think of whether a reader might say in their head, “Why doesn’t she just ______________?” If a character can just [fill in the blank] and the conflict is neutralized, you have more work to do.

Is this a conflict anyone would care about? This doesn’t have to mean the fate of the world must lie in the balance or lives are at stake (though they might be). Even a very small conflict can be riveting if we are emotionally invested. One of my favorite examples of this is found in John Cheever’s short story, “The Swimmer,” because it’s not even clear at first what the conflict could possibly be. It’s just a man swimming his way home from a party through other people’s pools. Go read it and see what I mean.

Are there opportunities to develop themes that will resonate with readers today? I have been attracted to a lot of ideas that would have worked better in times past. I think a lot of us who lived in libraries as children or who loved the classic literature of English class may find ourselves telling stories to previous generations rather than our own. Is your idea something that will engage the emotions and intellect of people in our current cultural setting?

Which brings up another important question: Who is my ideal reader? What kind of person would read this story? Does that kind of person buy and read books? In my own situation, my readers tend to be women ages 30-70. Lucky for me, they read a lot of books and they participate in book clubs, which my books are perfect for. But they are not the only readers out there. Check out this interesting study shared by The Fussy Librarian about reader demographics during the first year of Covid (you know, when everyone remembered that books exist).

Okay, these are just some of the questions you can ask yourself to determine whether an idea is worth pursuing. You also need to ask yourself the following:

Is this idea big enough to sustain a novel? Or would it be better as a novella or short story? If it’s not big enough, but I want to write a novel, how can I combine this idea with other ideas, concepts, and characters to make it bigger? (Bigger doesn’t just mean longer. It means bigger. Higher concept, higher stakes, more developed characters, more salient themes, etc.)

Will this idea require research? How much? Am I interested in the topics I’d have to research, or will I hate the entire process?

Is this idea appropriate for me to write? In other words, do I risk appropriating someone else’s story? For example, if I am a white, heterosexual woman from a white collar family who grew up in the suburban Midwest, am I the right person to tell the story of a poor LGBTQ+ refugee of color from a war-torn country struggling to survive on the streets of New York City? Unlikely. I don’t think I could do the necessary work to truly understand that person’s experience enough to be able to write authentically from that perspective. BUT, I might be able to write a story about such a character through the eyes of a protagonist who is more like me. Maybe I could be the Scout to this Tom Robinson. Maybe I could be the Nick Carraway to this Gatsby. Maybe I could be an insider who is learning from the outsider, a privileged person learning from an underprivileged person. It’s still going to take a LOT of work not to tokenize or stereotype this character in the telling. But it can be done. Am I willing to do the work to make it work?

Bottom line: Not every idea is worth putting in the time and effort to pursue. But a little reflection (and a little help from your writer friends) can help you weed out the weak ideas in order to make room for the strong.

As I close this first post of Experimental Wolves, I want to thank the 26 people who subscribed in the past 24 hours. I hope you’ve found this post helpful, and I look forward to building up this community of writers in the coming months and years!

For this first post, I’m allowing comments from all subscribers, free and paid, so please comment and get the conversation started. Do you have tips for recording ideas? How about for knowing which ideas to pursue? Do you have more time than ideas? Or too many ideas and not enough time to develop them into stories?

Great article. In my writer’s group were talking about this idea of how to decide about a conflict in the story arc and if it’s one people will care about and if it’s complex enough! Thank you